The lineage of the daughters of bankruptcy Women

[ad_1]

“Speak into the microphone, darling,” said the mother.

My dad passed me a small microphone that was directly connected to my mother’s headphones. I held my breath for a moment, stopped the vertigo, then rubbed the back of my head to relieve the pain. A what a couple we are, I thought to my heart, in this new appearance of mine, shooting too fast. We both disinherited from the world we once knew. Both of us, I imagined, were scared and lonely. Me for sure. But my parents were English, and we didn’t have to speak with difficult or unpleasant emotions unless we were forced to, and we could endure a lot of strength.

I directed my concentration to the menu.

“Pesto with a pen,” I began.

My mother tilted her head, focusing on something far away, as the cat follows the light in the shadows.

At a young age, my mother was tough: digging gardens, camping in the mountains, spending nights at her church to help the homeless. Growing up in London during the war gave him that bombardment-enable-us-but-still-going-out-dance mentality. But now, among other things, he was deaf and blind at the same time, and I returned to Michigan to be his eyes and ears. Or so I expected.

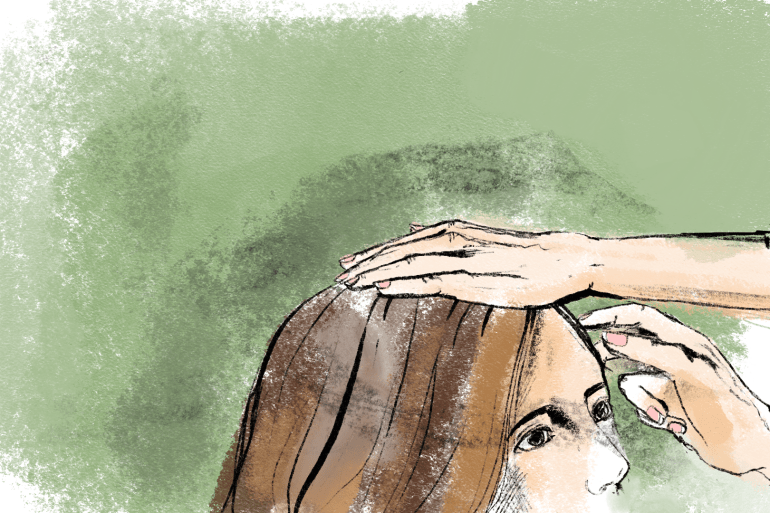

As I inherited my mother’s spirit, I traveled the world, boxing, dancing until four in the morning, under the tutelage of prisoners, marrying a little rock star and then divorcing, living on the Lower East Side for 25 years, sometimes teaching hard. neighborhoods, they sided with those in need. But now that he’s back in Michigan, an old head injury that didn’t heal properly accidentally ruined my life. I was in a lot of pain, dizziness, amazing memory loss, daytime insomnia, and so on. Suddenly, instead of coming to my mother’s house, I felt compelled to mother myself.

But my mother couldn’t help me more than I helped her.

There were only 41 miles between us, and yet we couldn’t get to each other unless my dad drove me. We called every day, trying to push each other, but I think leaving the other one as well. Terrified by what was happening in my body, I wanted a mother to investigate the latest findings about head injuries and talk to doctors on my behalf. He also wanted a daughter who would take care of his dowry: who could go for a drink and have long conversations, who could go shopping and join him for a manicure, as bringing food was now a culinary challenge.

“I’m an evil daughter,” I cried over the phone to my friends, lying on my brown velvet sofa, my thoughts dampened by the mist that surrounded my brain. “My mother needs me.”

This was an undeniable truth: he did.

I sensed that, but I also knew it because he told me so often.

“The church is doing wheel sales,” he said. “I have to sort out all the clothes that don’t fit anymore. I’d love to come and help me. ‘

Or: “My fingernails are messy and your dad can’t take me to Lisa this week. I’d rather you drive me. ‘

Or: “Tonight we’re going out with Uncle David and Aunt Zena. It would be nice if you could join us. ” His voice was heavy with longing and love.

I listened, my chest tightened, my stomach tighter, and I struggled to keep my despair away from the injustice of my life. There was my mother, waiting for me to get well so I could help her. And I was here, waiting for my cousin to take me to the store so I could pile up toilet paper because I couldn’t drive, or take my neighbors to my doctor for help with my brain’s disturbed neural pathways. .

“I’m sorry,” I told my mother several times. “I wish I could do all these things for you. And more. “

“Oh, my darling,” he said, his perceived despair rising. “Of course.”

And in those moments, I knew that my mother loved me with the savagery of deep bones. I deserved the love I questioned.

Then one day, when he and my father were finished, and I apologized again for not being able to go home, my mother said, so gently, so lovingly, shaking her hand, “Don’t worry, darling. I also left my mother. ‘

When my mother and father emigrated from London, they left their beloved mother behind. A few months after settling in America, after a few letters and phone calls, his mother died in a bad heart.

“I didn’t have to give up,” he lamented as I grew older, ruined by my mother’s death.

“Do you think leaving England killed your mother?” This kind of reasoning felt darkly magical in my young mind. The deadly power of a daughter’s neglect.

“He needs me,” he said, throwing circles of smoke over my head, his fingernails always in the perfect red color. “He needed me, and I failed him.”

[Jawahir Al Naimi/Al Jazeera]

[Jawahir Al Naimi/Al Jazeera]And here’s finally proof of my primary truth: I was the daughter my mother loved but didn’t need.

I doubled my healing efforts, I put tremendous pressure on my body, I raised my anxiety in an attempt to speed up what only doctors are pushing me to do: health. And I improved. Eventually the pain subsided, the vertigo subsided, and I began to sleep for more than three hours a night. But the neurological misconceptions I had about the world and the wet weather kept my brain from thickening at full speed, so driving was still hard.

In hard times, I would send each day cards with a special wish for my mother. On good days, I would rather go to my parents. Once there, through the thick, heavy fog of my brain, I sorted out the clothes infused with Chanel number 5 to look for stains, made sure her makeup matched her skin tone, arranged the jewelry box so I could find things by touch, I did my best. I came up with some really interesting stories from my life, and I listened to his stories, both the ones he embroidered to hide his sadness and the ones that kept the truth.

When it was time to leave, my mother was uncomfortably close by so she could see part of my face. His headphones were ringing. His eyes were grateful.

“I had the most wonderful time,” she said, as a mother would do to a healthy daughter. “Thank you, darling.”

“Come back anytime,” my father said enthusiastically, as his father would do to a daughter who could get into a car on a whim.

I was relieved to have been helped, but I already felt the pressure running through my heart to do everything again. And can I? The inability to make the love I felt consistently eroded me.

As my mother’s death approached a few years later, my health improved further, but it was still difficult to drive. In those last few weeks, we put her bed in my parents ’dining room and my family and I took turns in 24-hour shifts. Friends volunteered to guide me when I couldn’t. I knew then that I could let my guilt separate me from my mother’s dire needs, or that I could gather in branches and strings and move away from the nest until it was time to become on my own. I chose the latter. Once at home my mother bathed, boiled eggs, massaged her feet, read her stories, danced with her while she sat in her favorite favorite chair, and listened to her thoughts about her embarrassing death.

One day before I went home, I kissed him goodbye and said, “I’m going now. But I will carry you in my heart. ‘

Her eyes widened.

“I’ll take you to heart, too,” he said happily. Then he paused. Then, “Are you my daughter?”

This was talking drugs, of course. But it turned me on when I wrapped the blanket around my shoulders and then closed the curtains.

[Jawahir Al Naimi/Al Jazeera]

[Jawahir Al Naimi/Al Jazeera]And yet another day, here’s another thing my mother told me, brushing her hair from her face, her nails perfect French manicure: “I’m so glad you’re my daughter. I wouldn’t change anything about you. “

In the end, it was my mother who found me. I woke up my father, told him to pray, then bathed his body, anointed it with oil, while my father called his friends and relatives. Alone with him, in that misty morning light, as I washed his pale, shrunken arms as he soaked his legs in a flowery night — I had helped him choose a strange shopping expedition a few months earlier — I felt his feet bathe. he lightened the rope around the nest and held on to the crushing of the delayed penance.

But he did not come.

Instead, a flood of love surrounded me – for me and my mother: we were both trying hard. I didn’t fail my mother. Maybe I couldn’t give her everything she needed and wanted, but what mother is capable of having everything at all times? If I were healthy, would I be able to satisfy all his needs? Oh dear, repeated my now-living mother – and at last the words became cellular: I am glad you are my daughter.

Sometimes under the greatest despair lies unexpected absolution. Absolution is so sweet and so violent that it erases everything that came before and replaces it with grace. And the last time I combed my mother’s bedside hair, I felt like our daughters ’shared lineage had disintegrated; I felt our legs rise.

[ad_2]

Source link