UK’s services sector starts to count the real cost of Brexit

[ad_1]

Ross Patel is an exporter. But his stock in trade is not fresh food or car components in crates. It is musicians in minivans. Even so, like his counterparts in UK farms and factories, Patel is running into problems at the EU border.

Since the UK left the EU on December 31, Patel has been immersed in the jargon of cabotage, carnets and country-specific work permits as he tries to work out how travelling musicians can continue to ply their trade in the EU. Electronic trio Elder Island, the biggest act he manages as co-founder of music talent agency Whole Entertainment, are planning a 17-date tour of EU countries next year. Postponed three times already because of Covid-19, the tour has fallen into the tangle of regulations that now apply to UK exporters.

“We’re already losing money on this tour because of the impact of Brexit,” he says. “I don’t know how we’re going to make it work.”

Another musician, Simone Marie Butler, bassist with the well-established rock band Primal Scream, says less well-known groups now “have to be really well informed before saying yes to festivals and booking stuff: you can’t just drive to Europe or get on a flight to do a gig any more”.

The services sector accounts for around 80 per cent of the British economy, stretching well beyond finance to include fashion, tourism, auditing and architecture. Yet throughout the tortuous process of negotiating Britain’s departure from the EU, the services sector was rarely a priority — with the exception of the City of London.

The Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) struck by the EU and UK at the eleventh hour last Christmas was short on detail in many areas, but it was particularly threadbare in services.

“The extent to which the UK government prepared UK businesses for the change was inadequate, and [that is] particularly true of services businesses,” says Sally Jones, EY’s UK specialist on trade policy.

But with travel restrictions starting to be eased as vaccines are rolled out across Europe, the impact of Brexit on the UK’s services industries is starting to be felt.

Musicians are merely the most vocal, and visible, representatives of the UK’s vast services sector. These eclectic businesses share some common complaints as they get used to the new Brexit landscape: obstacles to cross-border mobility; a lack of government support and guidance; and a sense that much heralded opportunities outside the EU will not offset the potential loss of business in their closest big market. And like live music, the bigger groups are better able to absorb the changes and costs than smaller ones.

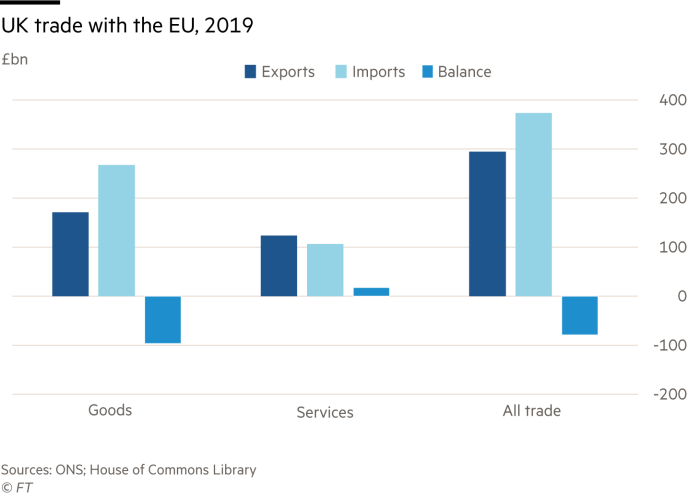

The lack of attention to services by negotiators is hard to explain. Services account for nearly half of all UK exports. That is a higher proportion than any other major economy. Questions over how to achieve equivalence in the EU for the UK’s financial services sector have commanded a lot of government attention. But the financial, insurance and pension sectors’ contribution of £29bn to UK exports to the EU in 2019, was outstripped by £41bn of exports of “other business services”. “Personal, cultural and recreational” services, including Elder Island and Primal Scream’s contribution, accounted for an additional £1.5bn.

According to analysis by McKinsey, in many service sectors, smaller businesses make up a higher proportion of exporters to the EU than they do among businesses exporting goods. Small businesses employing fewer than 50 people made up 94 per cent of all service-exporting businesses in 2018 and accounted for around 15 per cent of the turnover of all service-exporting businesses.

Larger companies are in a better position to shoulder the friction and just march on,” says the University of Sussex’s Ingo Borchert, deputy director of the UK Trade Observatory.

Britain’s skillsets

During the noisy transition period to Brexit, some critics of the EU maintained that its single market, opened in 1993, was still patchy at best, with outstanding barriers to service providers at member state level and uneven mutual recognition of qualifications.

But even incomplete, the EU is unique among trading blocs for the overlapping benefits it offers those inside the market, combining freedom of movement, mutual recognition, rights of establishment and free flow of investment.

One proxy for the depth of the EU single market in services is provided by an OECD index using data from 2014-2018, which allows comparison between restrictions imposed on the services traded between 25 members of the European Economic Area (including the largest EU countries) and those imposed on third countries wishing to trade with the EEA. On a scale of 0 to 1, where 0 is completely open and 1 totally closed, the intra-EEA average is 0.06 while the average for trade with third parties 0.22.

Borchert believes that the increasing share of services in UK exports over the past 30 years may in part have reflected the UK’s access to that deep EU pool, particularly in skill-intensive areas — law, auditing, advertising, consulting — where the UK has a comparative advantage. The question, he says, is whether the UK services sector can sustain its previous upward trajectory from outside the EU.

The main text of the EU-UK agreement appears to commit the trading partners to mutual guarantees on services. But the annexes contain multiple detailed reservations, which were raised by individual member states and are dotted through the document, in the words of EY’s Jones, “like some sick Easter egg hunt that the trade negotiators are sending you on”.

Not all these reservations affect the UK. Lord Gerry Grimstone, a UK minister, told a House of Lords inquiry into post-Brexit trade in services this year that Finland had underlined its right to allow only EEA nationals living in reindeer herding areas to “own reindeer and exercise reindeer husbandry”.

In other areas, though, businesses operating in regulated areas are likely to feel the impact of the patchwork of national reservations. Amanda Tickel, who heads Deloitte’s Brexit insights team, pointed out to the same inquiry that UK accountants must now have an EU base to sell their services to Slovenia; patent agents need EEA residency to operate in Finland and Hungary; and Cyprus requires residency for partners or shareholders of Cypriot companies.

The price of access

Regulated services businesses are likely to be worse affected than their unregulated counterparts. In a recent survey for London First, a lobby group for the UK capital, the highest levels of post-Brexit disruption, actual and anticipated, were reported by respondents in more regulated areas, including the accounting and legal sectors.

Jones uses tax as an example. Tax advisory is not a regulated profession in the UK, but advisers are regulated by some of the 27 EU member states. As a result, UK tax advisers must now first ask themselves, country by country, if there is any regulatory reason that they cannot offer their counsel to EU clients, whether they can then travel to the EU to provide services and, if not, whether they can serve clients remotely. In a few cases, the answer will be “no” on all counts.

Similarly, UK auditors who do not already operate an EU network can no longer set up on the continent, because their UK qualifications are not recognised in the single market and an EU directive requires audit firms to be owned by EU-qualified partners.

![Sally Jones, EY’s UK specialist on trade policy: ‘The extent to which the UK government prepared UK businesses for the change was inadequate, and [that is] particularly true of services businesses’](https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/https%3A%2F%2Fd1e00ek4ebabms.cloudfront.net%2Fproduction%2F9389f375-7449-4f07-b6c7-df0b2c4c5282.jpg?fit=scale-down&source=next&width=700)

UK lawyers are marginally better off. They can practise temporarily in the EU under their home-country professional title, a right enshrined in the TCA. Even so, UK lawyers might still need to requalify to regain privileged rights of audience in areas of practice important to them, such as intellectual property and competition law.

In non-regulated services businesses, Sam Lowe, senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform, a think-tank, says, “The difficulties are more indirect: if [a UK advertising agency] wants to be serving clients in Italy from London, you want to have Italians on staff. The new [UK] immigration system makes it more difficult to hire [EU nationals].”

All services businesses face new obstacles to moving freely around the EU without a visa or work permit. “You can do meetings and talks, but anything that involves direct payments is pretty much not allowed,” says Lowe. Rules for non-EU nationals restrict stays in the EU to 90 days in every 180 and cap contract terms at 12 months.

Covid restrictions have so far damped the impact of restrictions on free movement, but Jones says she is “already seeing evidence that immigration authorities in certain countries are taking this pretty seriously”. Some immigration authorities, she says, may apply a “three strikes” policy: a warning for the first breach of new rules, a fine for the second breach and a ban after a third offence. The application of immigration rules “isn’t just an idle threat; it’s genuinely happening”, Jones adds. EY says UK firms are already investing hours to ensure compliance with the EU mobility rules.

Supporting SMEs

As the dust settles on the TCA, and recriminations over the negotiating process fade, the common short-term demand of UK services exporters is for more coherent UK government guidance through the national reservations that pockmark the agreement. The House of Lords committee looking at services trade last month urged the government to provide this advice “as a matter of urgency”. According to a government spokesman, the UK is already “operating export helplines, running webinars with experts and offering businesses support via our network of 300 international trade advisers”, on top of its £20m Brexit support fund for small and medium-sized enterprises.

The CER’s Lowe suggests Brexit has “focused minds a little bit”, so both services businesses and the UK government are likely to put more effort into export promotion outside the EU. Some sectors have won exemptions. Unlike their counterparts in the live music business, for instance, UK filmmakers will benefit from an explicit commitment in the TCA to tariff-free movement of film equipment across the EU for specific film shoots.

Lockdown has already obliged many small companies to rethink the need to cross borders to transact business that can be done remotely. That may mean they can avoid stricter frontier controls. UK regulators of some professions — architects, for instance — have collaborated with EU counterparts to replicate at least some elements of mutual recognition.

But there may be unintended long-range negative consequences. Borchert draws attention to the large chunk of services exports accounted for by foreign-owned businesses, including manufacturers that bundle aftersales services into goods they export to the EU from the UK. Over time, he suggests, “one of the more subtle effects of these new [post-Brexit] barriers is that they might diminish the incentives for these kind of inbound investments”.

Similarly, larger services businesses may choose to expand their staff in the EU rather than in the UK. Stephen Denyer, director of strategic relationships at the Law Society of England and Wales, says London law firms with a European presence will stick with their global strategy, but may gradually start to favour EU nationals for partner promotion over UK passport-holders.

For now, it is too soon to pick out much impact of the UK’s departure from the EU from trade data. New ONS analysis suggests service businesses reported a temporary decline in exporting, compared with normal expectations, between mid-December and mid-January, which may represent a Brexit effect.

But the pandemic will also muddy the statistical evidence of Brexit’s effect for a while. Economists say it will always be hard to compare what might have been with what takes place. Among service providers, though, there is a queasy sense that trade with the EU has become, at least temporarily, harder, and that their rich services offering has become a little less attractive to EU customers.

As Primal Scream’s Butler puts it, in future, before EU festival organisers book UK bands, are they going to ask themselves: “Is it worth the trouble?”

[ad_2]

Source link