Rate expectations: Developing economies threatened by US inflation

[ad_1]

While developing politicians around the world are fighting the ongoing spread of coronavirus, they are also facing the economic threat of inflation, and not just at home.

Rising prices in major economies, especially in the US, are fueling expectations of rising rates for investors. This increases bond yields, and it is more expensive for other countries to sell debt because buyers are demanding higher returns.

What should be good news – the beginning of the global recovery – has become a threat: borrowing costs will reach dangerous high levels in countries like South Africa and Brazil, and already precarious public finances will be dismantled.

Inflation: a new era?

Prices are rising in many major economies. The FT examines whether inflation has finally returned.

DAY 1: Advanced economies have not coped with rapid inflation growth for decades. Is that about to change?

DAY 2: Global consensus among central banks on how best to promote low and stable inflation has broken down.

DAY 3: Canary from the coal mine due to US inflation: used cars.

DAY 4: How the virus has been interrupted official inflation statistics.

DAY 5: Why they are raising prices in advanced economies for developing countries that are borrowing.

“Emerging economies should be more concerned about U.S. inflation than about inflation,” said Tatiana Lysenko, chief economist at S&P Global Ratings ’new markets.

It’s not just inflation and rising U.S. yields that drive up development borrowing costs, he said. The biggest risk is that the U.S. economy will have power ahead of emerging economies, outflows of their shares and bonds, and ultimately create currency weakness.

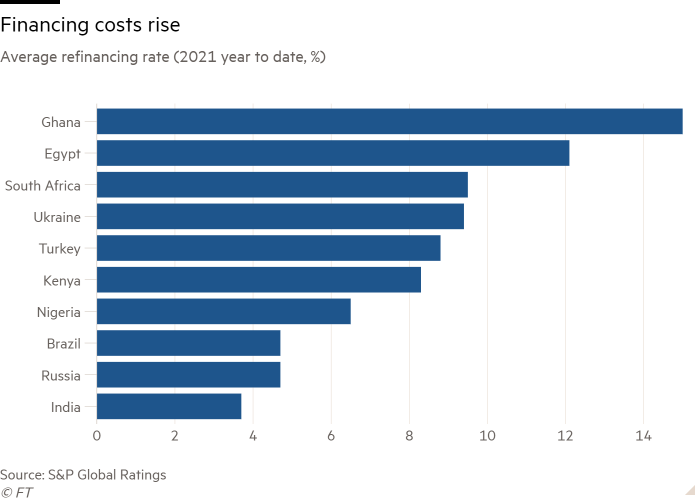

Although rich countries have been able to borrow at very low rates during the pandemic, many developing countries already have a much higher cost of financing.

S&P data show that refinancing costs in 15 of the top 18 developed economies have fallen by more than one percentage point below the average cost of borrowing. Most pay a 1 percent share. A 1 percentage point increase in funding costs would be easy for most.

The same cannot be said of developing countries. Egypt, which has to refinance 38% of its gross domestic product debt this year, is paying an average rate of 12.1 percent, above the average cost of 11.8%, according to S&P. Ghana is paying 15 per cent, an average of 11.5 per cent.

The risk is not at very high rates. Brazil has refinanced an average rate of 4.7% this year, lower than the average cost of existing debt. But he did so by selling bonds that needed to be repaid faster than in the past.

This undoes the work of the years when Brazil sold a longer rate and a fixed rate, making its finances more sustainable. Last year the average maturity of his new debt was two years, down from five in 2019.

Brazil needs to refinance its debt to 13% of GDP this year – a smaller proportion than smaller nations, but a higher total amount, and could offset rising rates or a slower-than-expected recovery.

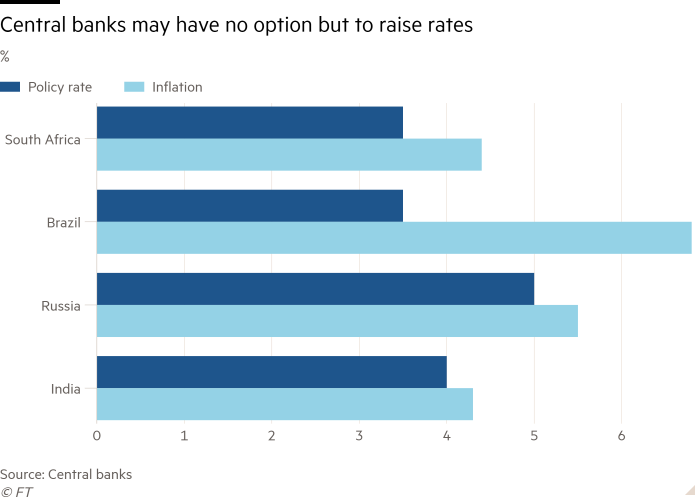

Its central bank has doubled rates this year in an effort to ease price pressures after inflation exceeded the target of 2.25 to 5.25 percent. Another increase is likely at the next meeting next month, and is forecast to hit a base rate of 5.5 percent by the end of the year, with a low of 2 percent in March.

Brazil is a clear example of how inflation and rising profits are a threat to debt sustainability, said William Jackson of Capital Economics. “Public finances, rising inflation and rising central bank rates have stretched, fueling the cost of debt services.”

South Africa is in the same category, he said, along with Egypt and others in dire need of refinancing.

There are mitigating factors. For example, Brazil, South Africa, and India rely much more on domestic lenders than on foreign ones. This makes them more vulnerable to capital outflows in the twentieth century. In the debt crises of the turn of the century.

India, in particular, has relied on its home banking system to issue 10-year benchmark bonds with limits of around 6 per cent. It has also borrowed at shorter maturities during the pandemic, although with a low refinancing requirement this year – equivalent to 3.3% of GDP – it is less vulnerable to rising rates.

But William Foster, chairman of Moody’s Investors Service’s sovereign risk group, said India’s fiscal problems depend on debt instead of government revenue to fund its pandemic response.

“India has huge fiscal deficits and a huge debt,” he said. “The most important thing for debt sustainability is to achieve a higher growth rate in the medium term through reforms and other measures to include private investment that we have not seen over the years.”

As many politicians expect, if inflation rises temporarily this year, interest rates on emergency economies may not rise by far.

Roberto Campos Neto, the governor of Brazil’s central bank, told a conference this week that the problem was temporary inflation and was justified by growth or that central banks had to raise rates further. “The first case is beneficial for the emerging world,” he said. “The second one isn’t.”

Lysenko said food and commodity prices are rising at a rate that is fueling consumer inflation expectations. If interest rates rise significantly, reducing the debt of developing economies to sustainable levels – and achieving growth – will be much more difficult.

“In an interconnected world with a lot of capital flows, U.S. profits have large outflows,” he said. “It’s early [for emerging markets] squeeze [monetary policy], doing so can now recover. But maybe some countries don’t have much time left to tighten up. ‘

[ad_2]

Source link